Co-reporter: Pouya Javidpour, Tyler Paz Korman, Gaurav Shakya, and Shiou-Chuan Tsai

pp:

Publication Date(Web):April 20, 2011

DOI: 10.1021/bi200335f

Type II polyketides include antibiotics such as tetracycline and chemotherapeutics such as daunorubicin. Type II polyketides are biosynthesized by the type II polyketide synthase (PKS) that consists of 5–10 stand-alone domains. In many type II PKSs, the type II ketoreductase (KR) specifically reduces the C9-carbonyl group. How the type II KR achieves such a high regiospecificity and the nature of stereospecificity are not well understood. Sequence alignment of KRs led to a hypothesis that a well-conserved 94-XGG-96 motif may be involved in controlling the stereochemistry. The stereospecificity of single-, double-, and triple-mutant combinations of P94L, G95D, and G96D were analyzed in vitro and in vivo for the actinorhodin KR (actKR). The P94L mutation is sufficient to change the stereospecificity of actKR. Binary and ternary crystal structures of both wild-type and P94L actKR were determined. Together with assay results, docking simulations, and cocrystal structures, a model for stereochemical control is presented herein that elucidates how type II polyketides are introduced into the substrate pocket such that the C9-carbonyl can be reduced with high regio- and stereospecificities. The molecular features of actKR important for regio- and stereospecificities can potentially be applied in biosynthesizing new polyketides via protein engineering that rationally controls polyketide keto reduction.

Co-reporter: Pouya Javidpour, Abhirup Das, Chaitan Khosla, and Shiou-Chuan Tsai

pp:

Publication Date(Web):July 21, 2011

DOI: 10.1021/bi2006866

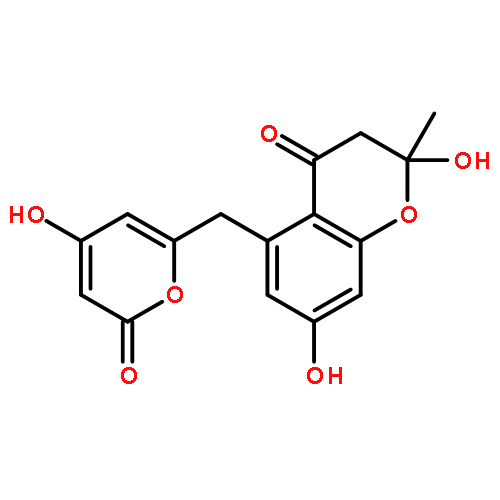

Bacterial aromatic polyketides that include many antibiotic and antitumor therapeutics are biosynthesized by the type II polyketide synthase (PKS), which consists of 5–10 stand-alone enzymatic domains. Hedamycin, an antitumor antibiotic polyketide, is uniquely primed with a hexadienyl group generated by a type I PKS followed by coupling to a downstream type II PKS to biosynthesize a 24-carbon polyketide, whose C9 position is reduced by hedamycin type II ketoreductase (hedKR). HedKR is homologous to the actinorhodin KR (actKR), for which we have conducted extensive structural studies previously. How hedKR can accommodate a longer polyketide substrate than the actKR, and the molecular basis of its regio- and stereospecificities, is not well understood. Here we present a detailed study of hedKR that sheds light on its specificity. Sequence alignment of KRs predicts that hedKR is less active than actKR, with significant differences in substrate/inhibitor recognition. In vitro and in vivo assays of hedKR confirmed this hypothesis. The hedKR crystal structure further provides the molecular basis for the observed differences between hedKR and actKR in the recognition of substrates and inhibitors. Instead of the 94-PGG-96 motif observed in actKR, hedKR has the 92-NGG-94 motif, leading to S-dominant stereospecificity, whose molecular basis can be explained by the crystal structure. Together with mutations, assay results, docking simulations, and the hedKR crystal structure, a model for the observed regio- and stereospecificities is presented herein that elucidates how different type II KRs recognize substrates with different chain lengths, yet precisely reduce only the C9-carbonyl group. The molecular features of hedKR important for regio- and stereospecificities can potentially be applied to biosynthesize new polyketides via protein engineering that rationally controls polyketide ketoreduction.